Brett Busby ’98 Appointed to Texas Supreme Court

A Columbia Law professor’s advice turned Brett Busby’s career interests from tax law to appellate work.

After spending nearly two decades in appellate courts as a lawyer and a judge, Brett Busby ’98 relishes the variety of legal issues he has been involved in, from the First Amendment to securities law. It’s a wide-ranging career that stems from a single turning point: A Columbia Law professor casually told him, “You ought to try clerking.”

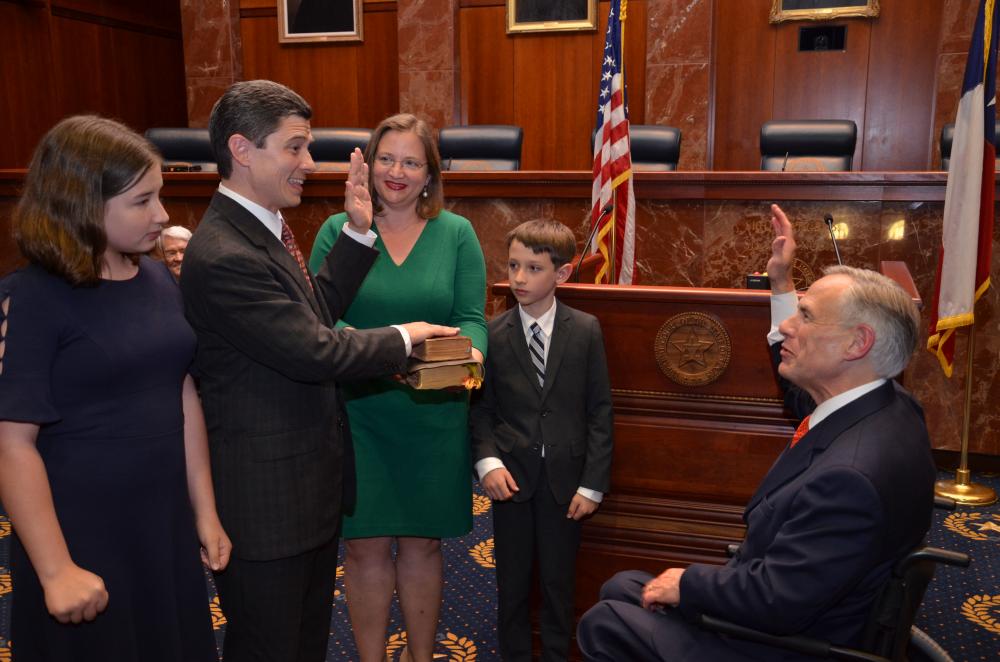

He did. Busby launched a career in appellate law by clerking for Judge Gerald Tjoflat of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit and U.S. Supreme Court Justices John Paul Stevens and Byron White (then retired). In March, he joined a high court himself: Texas Gov. Greg Abbott appointed him to the Texas Supreme Court.

Busby is now one of five Columbia Law alumni on state high courts, joining Chief Justice Thomas Saylor ’72 of Pennsylvania, Justice Lindsey Miller-Lerman ’73 of Nebraska, Justice Barbara Lagoa ’92 of Florida, and Justice Jenny Rivera ’93 LL.M. of New York.

“It’s certainly a dream job for me,” Busby says, since the Supreme Court had been “grading my papers” during his six years as a state appellate judge. “It’s very exciting to be able to join them.” Busby now hears only civil cases (Texas and Oklahoma are the only states that separate their highest court into civil and criminal benches). In 2018 he was named Appellate Judge of the Year by the Texas Association of Civil Trial and Appellate Specialists.

His elevation to the high court came after a low point: In November’s state election, Busby, a Republican, lost his seat on the Houston-based 14th Court of Appeals when a Democratic wave swept new majorities of Democratic justices onto appellate courts in Houston, Dallas, and Austin. With 59 judicial positions on the ballot, Busby says, it was hardly likely that voters would make candidate-by-candidate decisions. Instead, a substantial majority of voters cast a straight-party ballot, in which voters use a single vote to cast ballots for all of a party’s candidates. “Even lawyers don’t know all those people,” he says. “It was disappointing to lose, but in an environment like that you can take comfort in knowing it had nothing to do with you.” (In 2017, Texas voted to abolish straight-ticket voting in 2020.)

A New Career Trajectory

Sitting on the bench was not in his plan when Busby arrived at Columbia Law School. After earning an undergraduate degree in public policy and international affairs from Duke University, he planned to pursue international law or tax law, areas of study for which Columbia Law has long been known. Then Busby took a seminar on statutory interpretation with John Manning, Columbia Law clerkship adviser at the time and now the dean of Harvard Law School, who recommended he clerk.

“It totally changed the trajectory of my legal career,” Busby says, “just because he suggested that to me. I really like the research and writing, and the way that you persuade in appellate work.” He also loved the variety of appellate cases. “It’s always something new, and you’re always learning,” Busby says. “There are very few generalists left in the law these days, but appellate judges are some of them. I really do enjoy that.”

Busby’s interest in litigation also developed at Columbia, when he worked for an immigration clinic. “That was very satisfying,” he says. “Ever since then I have thought that clinics are a really wonderful way for students while they’re in law school to gain practical skills of seeing what it’s like to actually practice law. I think that really gave me a leg up.”

He gave tax law a last shot, working as a summer associate at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton. But he found he was a generalist at heart. “I was concerned I’d get five years into a tax career and say, ‘Well, now I’d like to do a different kind of case.’” In Texas, where Busby’s roots date to the Texas Republic, appellate law was a well-developed practice specialty.

It was thanks to his Supreme Court clerkship that Busby met his wife, Erin Glenn Busby, who clerked for Justice Stephen Breyer. During the same time, it was thanks to Justice Sandra Day O’Connor that Busby, a violinist, met a rare musical instruments collector who let him play a Stradivarius and a Guarneri. “It was just about the greatest experience any violinist could have,” says Busby, who now plays with the Houston Civic Symphony.

Taking on a Judicial Role

A member of the conservative Federalist Society, Busby says his judicial philosophy was most influenced by a case he lost at the U.S. Supreme Court: Day v. McDonough in 2006. Busby’s pro bono client, convicted of second-degree murder in Florida, had been denied a habeas petition because a lower court ruled it had not been filed in a timely fashion. Busby’s argument, that the state of Florida had not flagged that issue and therefore the court should not raise it of its own volition, was rejected 5-4.

The decision has been central to Busby’s approach on the bench. “It’s not up to the judge to be the lawyer for one side and raise an issue they haven’t raised and decide the case on that basis,” he says. In law, “we have an adversary system. We’re there to judge the issues the parties raised, not to make arguments on their behalf.”

That’s why, in 2012, he ran for appellate judge. “I felt I had a pretty clear understanding [of] what the judicial role should be,” he says. “And rather than continuing to be frustrated as a lawyer when judges stepped outside that role, I had the ability to do something about it.”

Busby has also worked to make legal representation more accessible, through the Texas Access to Justice Commission, by trying to simplify procedural rules and the required forms for pro se litigants.

“We’re seeing a lot more people who are representing themselves in state court,” particularly in family court and in landlord-tenant disputes, he says. “It’s definitely an issue that is becoming more serious as the cost of litigation is going up. It’s unaffordable for more and more people.”

# # #

Published on July 30, 2019