Breaking Barriers at Columbia Law and on the Bench

Roderick “Rick” Ireland was one of only 13 black students in Columbia Law’s Class of 1969, as the school started recruiting from historically black colleges. A half-century later, he discusses his career and his legacy in the Massachusetts courts.

Law school had never occurred to Rick Ireland ’69. In 1966, as a senior at Lincoln University, a historically black school located outside Philadelphia, he had vague plans for some kind of graduate study at Howard University. Then he was asked to come to a meeting with Frank Walwer, an associate dean at Columbia Law whose mission was to diversify the overwhelmingly white institution at a time when fewer than 1 percent of the nation’s lawyers were African-American.

“By the end of the conversation I was in—hook, line, and sinker,” says Ireland, now a retired chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and a distinguished professor at Northeastern University. “It didn’t take too long for me to realize that this was a unique, special, life-changing opportunity.”

On the Massachusetts court, Ireland, in turn, created life-changing opportunity for others when he joined the 4-3 majority in the 2003 Goodridge v. Department of Public Health case. The court held that its state laws barring same-sex marriage were unconstitutional, the first state supreme court to do so. He also was the sole dissent in Cote-Whitacre v. Department of Public Health in 2006, which restricted same-sex marriage for out-of-state residents. The Massachusetts legislature subsequently enacted a law to allow same-sex couples from anywhere to be married in the state.

Ireland, like his fellow members of the Class of 1969, celebrates his 50th reunion this year. When he was first persuaded to consider a legal career, Columbia was one of the first major law schools to recruit applicants from historically black colleges. It still does so today.

Ireland’s conversation with Walwer left him eager to jump into the social upheaval of the 1960s as a public interest lawyer. It was a time, he recalls, when “there was a lot going on.

“I thought, almost from the beginning, I would like to be a lawyer who speaks up for disenfranchised people, for people who don’t have a voice,” he says.

Most of his classmates were looking at a partnership-track job. “Everybody I knew was trying to go with the big firms. There were just one or two of us who had any interest in doing public service,” Ireland says. “I was kind of the outlier.”

Challenging an Unfair System

After graduating in 1969, Ireland headed to Harlem to be a public defender, with the help of a Reginald Heber Smith Community Lawyer Fellowship, a program established to attract lawyers into poverty law. Two years later, he returned home to Massachusetts and, with another Heber Smith Fellow, co-founded the Roxbury Defenders Committee, a widely admired public defenders program.

In Roxbury, the young lawyers looked for test cases to help poor clients have a better shot in the criminal justice system, tackling “things going on that just seemed so unfair, we said we have to challenge that,” Ireland notes. One of his cases, for instance, led to indigent defendants receiving court transcripts at no cost. In 1977, he was appointed a juvenile court judge by Gov. Michael Dukakis. He rose to the Massachusetts Appeals Court in 1990, and, in 1997, he became the first African-American justice on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. He served as chief justice from 2010 to his retirement in 2014.

Just as he was recruited to the law, Ireland has tried to increase diversity among both lawyers and judges. He is president of Northeastern’s Justice George Lewis Ruffin Society, which supports advancement of students and professionals of color in criminal justice. Black law students and lawyers need mentoring and encouragement to put their hats in the ring for important assignments and for appointment to the bench, Ireland says.

“It’s more difficult [to move up] if you’re a person of color. I don’t want to say the deck is stacked. There’s always space for a qualified person, but one of my jobs was—and is—always to try to encourage people to take the risk, put your name in,” he says. Filling the “pipeline” of black lawyers, he says, should start as early as high school, getting young people to think about law school.

‘You Belong Here’

At Columbia, Professors Robert Cover and Maurice Rosenberg mentored Ireland when he faced the challenges of his 1L year. “I had to work really, really, really, really, really hard in that first year,” he says. “It took a while to figure it all out. How to study, how to write.” Constitutional law professor Herbert Wechsler “wasn’t friendly, but God, he was so good, and he was so challenging,” Ireland says. “When I took his course, that’s when I said to myself, ‘You know what? You belong here with these students. You may not be the brightest star, but you can hold your own here.’ And that stood me in good stead for the rest of my career.” (Nearly 40 years later, Ireland repaid the intellectual debt: He opened his dissent in Cote-Whitacre by citing Wechsler’s “Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional Law.”)

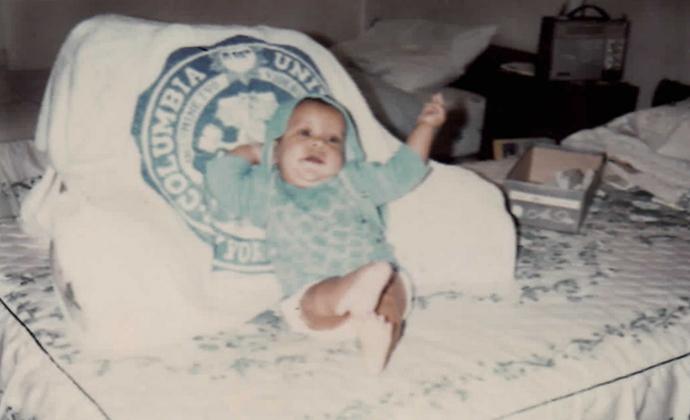

Making law school more complicated: Ireland was a parenting pioneer as well, which his classmates realized the day he showed up for Cover’s family law final exam with baby Helen Elizabeth in her stroller. Mom was in class at Barnard College, and the babysitter didn’t show.

“She was in a little diaper. She was wet, she was hungry. But I grabbed a banana, and I rolled her into Columbia Law School and rolled her right into the room where they were giving the exam, to the consternation of my classmates,” Ireland says. “The baby was making baby noises. I pretended like I didn’t hear anything, and I put my head down and started writing."

Nonetheless, both of them got the boot from the room, until a volunteer from the dean’s office came to watch over Ireland’s little girl. Dad returned to the exam and earned an A. “My friends say I got extra help: I brought my daughter.”

Decades later, when he became chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in 2010, Ireland set out to improve the judiciary’s relationship with the public, which, he realized, found most aspects of the legal process confusing. In court, “people don’t talk in English, they talk in legalese,” he observes. “The signs that are there are confusing. Who knows what Probate and Family Court deals with?”

Ireland felt legal jargon was more than just an irritant: It affected the lives of those appearing in court. “When I was a trial judge, I always broke [the proceedings] down into simple sentences to make sure that they [the defendant] understood each and every component of what was going on. And sometimes I would say, ‘Well, tell me what that means to you.’ And then I would find out they didn’t have a clue what it meant.”

Ireland implemented courthouse information booths, required court forms to be printed in multiple languages, and extended hours of some courts so that litigants could resolve their cases without having to miss work. Under Ireland’s leadership, the state Supreme Judicial Court also approved “limited access representation” to help litigants afford legal assistance. “My goal was to try to make the court experience more understandable to anyone who walks in the courthouse . . . so that it wasn’t such a puzzle, a mystery, a confusing ball of wax,” he says. “And I think we accomplished a lot of that during my time.”

Ireland’s impact on the courts did not end with his retirement from the bench: In 2017, the Hampden County Superior Courthouse in Springfield, Massachusetts, his birthplace, was renamed in Ireland’s honor as the Roderick L. Ireland Courthouse.

# # #

Published on April 17, 2019