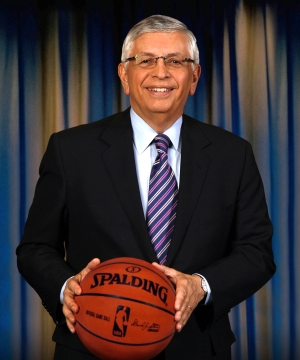

Off the Court with NBA Commissioner Emeritus David J. Stern ’66

2017 Medal for Excellence Winner is a Social Justice Champion

Columbia Law School’s most prestigious award, the Medal for Excellence, has been presented annually since 1964 to alumni and past or present faculty members who exemplify the qualities of character, intellect, and social and professional responsibility that the Law School seeks to instill in its students.

|

David J. Stern ’66 (left) speaks at a 2014 NBA Hall of Fame event. |

In the court of public opinion, David J. Stern ’66 is universally recognized as a visionary who transformed the National Basketball Association (NBA) into a global brand and $5 billion business during his tenure as commissioner from 1984 to 2014. A skilled negotiator who began his career in the litigation department at Proskauer Rose, where one of his clients was the NBA, he joined the league in 1978 as its 24th employee and its first general counsel. “I would not have left Proskauer if they hadn’t told me they’d welcome me back,” he says. “I thought the law and litigation was a great calling.”

Stern’s legacy extends far beyond the bottom line. “Contrary to certain economists who preached that the business of business was business, we came to believe that the obligation of businesses was social responsibility for their employees, their stakeholders, their shareholders, their local community and the greater community,” says Stern, who will be honored with the Columbia Law School Medal for Excellence at the Feb. 24 Winter Luncheon.

In his early days at the league, Stern faced skeptics who doubted the NBA’s potential to rival the popularity of Major League Baseball and the National Football League. “There were people at newspapers that took the position that the NBA could not survive because it was becoming increasingly African-American, and America would not accept an African-American sport,” he says. “We were digging out of some perceived hole. We adopted the position, because we believed in it, that sports were the ultimate statement of egalitarianism. That it didn’t matter who you were, the color of your skin or where you came from—if you had game, then you played.” Stern is fiercely proud that the NBA is a meritocracy. “We think that the focus on talent is a spectacular thing. It sounds trite, but it’s true: Wealth may be distributed by zip code but talent and IQ are not,” he says.

Like any effective leader, Stern turns challenges into opportunities. “There were two very important events that contributed greatly to both my understanding of the power of sports and the obligation of sports to use its celebrity to help society,” he says. “The first was when Magic Johnson announced in 1991 that he was HIV positive. By virtue of that announcement, and the league’s standing behind him and assisting communications efforts about the disease, we taught the world not to be afraid of people who are HIV positive. That was a seminal moment for me.”

The other transformative event was when Stern traveled to South Africa in 1993 and met Nelson Mandela, who encouraged his countrymen, as a sign of post-apartheid unity, to enthusiastically support the nation’s primarily white rugby team on its road to the 1995 World Cup. “He thought that sports was the one thing that could bring people together and deliver important messages,” says Stern, who notes that the rugby team’s story was turned into the 2009 movie, “Invictus,” starring Morgan Freeman and Matt Damon.

Johnson and Mandela made Stern increasingly aware that the league could be a forceful agent for change by enlisting the support of its fans. And to make fans feel deeply connected to the NBA, the league had to make fans feel it cared about them. “I used to tell the owners, ‘Public relations is what people think about you and community relations is how they feel about you’,” he says. “And that was an important part of the NBA’s outreach.” The league made alliances with numerous causes and organizations: Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign and President Reagan’s Council for a Drug Free America; hunger groups such as Share Our Strength; the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and the Special Olympics.

The response to the league’s civic-minded full-court press was overwhelming. “It seemed everyone was knocking on our door and thought sports was the answer to their problems,” he recalls. Some advised him that the league was spreading itself too thin and suggested that Stern would get “bigger bang for your buck” if the NBA affiliated with a single charity. “I said, ‘No, no, no, that’s not who we are’,” says Stern, who realized that the league needed an umbrella to codify its philanthropy and volunteerism. The solution was NBA Cares, a dedicated social responsibility program, which has constructed over 1,000 places where kids and families can live, learn, and play and supports—with millions of dollars raised and thousands of hours worked by the NBA and its players—myriad youth-serving programs that focus on education, family development, and health-related causes.

Stern’s commitment to public service has not been limited to the NBA. He served as chair of the Board of Trustees of Columbia University from 2000 to 2004, during the transition between Presidents George Rupp and Lee C. Bollinger ’71, which was an enormous time commitment. “It would not be accurate to say that it had no impact on my day job, but I thought it was important service,” he says. He serves or has served on the board of the NAACP, the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, the Paley Center for Media, the Columbia University Medical Center Cardiac Council, and Jazz at Lincoln Center. “Winton Marsalis recruited me by saying that jazz and the NBA were both particularly African-American cultural institutions,” he says.

Now that he is the commissioner emeritus, Stern is offering advice to the athletic directors at his two alma maters: Rutgers, where Stern received his bachelor’s degree in 1963, and Columbia. He’s offering his expertise on making deals with athletic shoe and apparel companies, television programming, sponsorship sales, and fundraising. And he’s been advising Columbia Law School on fundraising strategies. “There is a huge amount of untapped potential,” he says.

But Stern is not retired or retiring. He’s CEO of DJS Global Advisors and a senior advisor to the NBA, Greycroft Partners (venture capital), PJT Partners (investment banking), and PricewaterhouseCoopers (media and entertainment.) And he has spoken out in favor of legalized betting on professional sports, which is a new stance for him. “That’s not a priority, just a statement of my belief,” he says. “I did give a speech before the American Gaming Association and said that it’s time given the adoption of daily fantasy sports leagues and the huge amounts that are being illegally bet and feeding the pockets of organized crime. It’s probably a good thing to come up with a stratagem for legalizing sports betting, properly supervising it, and funneling the profits to government.”

As for the future of the NBA, he has full confidence in his handpicked successor, Adam Silver, whose father, Ed Silver, was Stern’s mentor at Proskauer. Coincidentally, the first recipient of the Medal for Excellence in 1964 was the legendary Judge Joseph Proskauer, Class of 1899, one of his old firm’s founders. “When one looks at the other recipients over the years, it’s really a judicial, legal, and academic hall of fame,” says Stern. “I am honored to be included with this group.”

###

Posted February 23, 2017