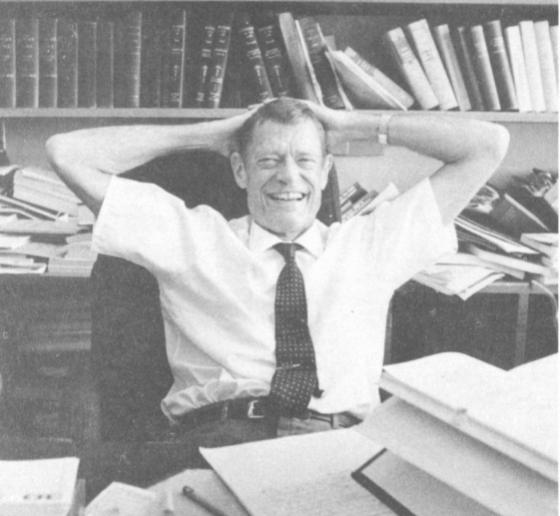

Professor Jessica Bulman-Pozen Honored With 2024 Willis L.M. Reese Prize for Excellence in Teaching

Students praise Bulman-Pozen for her scholarly expertise, communication skills, and genuine kindness. She will receive the prize, awarded annually by the Law School’s graduating class, and speak at graduation on May 13.

Students cannot say enough great things about Jessica Bulman-Pozen, Betts Professor of Law.

“JBP is low-key goated when learning admin law is the vibe,” wrote one student in a course evaluation.

The student also included a translation: “Professor Bulman-Pozen is an excellent lecturer and crafter of a curriculum.” Other students provide their praise more simply: “Just so brilliant,” “thoughtful and kind,” “incredibly engaging, presents content effectively, and masterfully explains difficult material,” and “by far the best I’ve had at CLS, and I think they were all good.”

This is the second time Bulman-Pozen has won the Reese Prize. The first was from the Class of 2015, which arrived at Columbia Law in 2012, the same year Bulman-Pozen began teaching here. “I’m passionate about teaching,” she says. “I care a lot about my students and about both teaching them and developing relationships with them during their time at law school.”

A leading constitutional scholar and expert in administrative law, federalism, and regionalism, Bulman-Pozen teaches courses that include Legislation and Regulation, and Constitutional Law, among other courses. “JBP was the best professor I have had in law school. Polite, respectful, caring, incredibly knowledgeable, and thought-provoking,” wrote one student in an evaluation. Another described Bulman-Pozen’s class as difficult, with a tough grading curve. “But the actual experience is about as perfect of a law school course as you can get.”

Students praise Bulman-Pozen for her flexibility in answering questions and bringing in relevant topics from beyond the scope of the day’s reading. Her seminars—such as a Public Law Workshop she has taught with Olatunde C.A. Johnson, Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 Professor of Law—offer more room for the latter, she says. “I try to respond to both what’s happening in the classroom and what’s happening in the world with respect to how I teach the classes.”

She uses a panel system for cold calls, assigning groups of students to be on call for a particular class session, to reduce the stress of being randomly called while still making sure everyone gets heard. “There are plenty of really sharp people who have great observations but will not share them unless I have already brought them into the conversation,” she says. She also bans laptops from the classroom. Requiring students to take notes by hand helps them process the material she is teaching, Bulman-Pozen says—and keeps news alerts and personal messages from pinging into the classroom. “It’s too much to ask of people not to be distracted,” she says.

Literature to Law

As an undergraduate at Yale, Bulman-Pozen majored in English; she chose to attend law school after completing postgraduate work in literature at the University of Cambridge. She suspected she might enjoy becoming an academic like her mother, a professor emerita of psychology at University of Massachusetts Amherst. But she had headed Yale’s student-led Center for Public Service and Social Justice—and the issues of the day beckoned through the pages of Milton and Wharton.

“I wanted my career to allow me to engage with real-world issues I cared about,” she says. “There was always a part of me that wanted to be active in more immediate problem-solving.”

After law school, she served as a law clerk to Merrick B. Garland when he was on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and also clerked for Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens. She also worked as an attorney-adviser in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel. Along the way, she married her Yale classmate David Pozen, who is Charles Keller Beekman Professor of Law at Columbia Law.

Since joining the Law School, Bulman-Pozen has published widely and serves as a faculty co-director of the Center for Constitutional Governance.

“I think I found the sweet spot—as a professor, I can engage in the research and writing and teaching that I love, but I can also write amicus briefs and help groups that I care about with their legal strategies,” she says. Issues she focuses on include voting rights and reproductive rights. “Being a professor is an excellent perch for doing all of those things.”

Knowing Everything

When she won the Reese Prize in 2015, Bulman-Pozen felt that, as the professor, she was supposed to know the answer to everything. “I was terrified of making a mistake when I started teaching,” she says. “I was worried about maintaining control and establishing authority and making sure I didn’t mess up in front of a hundred people.”

Almost 10 years on, she claims she still doesn’t know everything, but it worries her less. In fact, she views it as an important part of teaching.

“I know many things about the subjects I teach, and I try to convey that knowledge,” she says. “But I’m not afraid of students asking me questions I don't know the answer to. I take those questions as opportunities to engage with students in new ways.”

Working with students, whether in seminars or supervising their research and independent writing projects, is one of the most rewarding parts of teaching, Bulman-Pozen says. The relationships often continue after graduation. “I like to stay in touch with my students,” she says. “I try to be, for students who want it, a mentor or someone who can be confided in or just spoken to—not just about course material, but about the experience of law school, about their future aspirations, about their lives. I appreciate that no one is ever just a student.”