Community Book Read Launches With Biography of Constance Baker Motley ’46

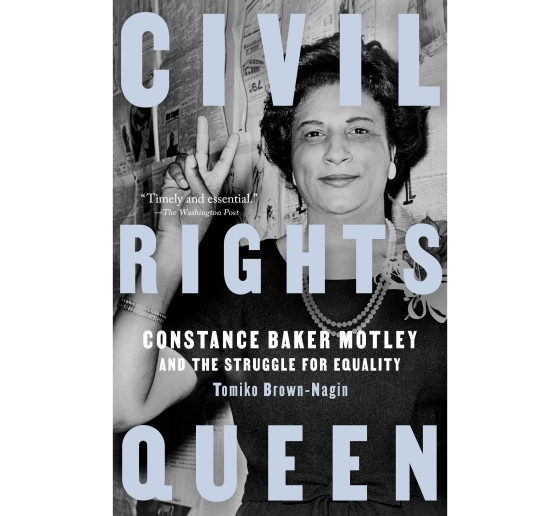

Author Tomiko Brown-Nagin visits Columbia Law School to discuss her book Civil Rights Queen.

Constance Baker Motley ’46, the second Black woman to graduate from Columbia Law School, had a prodigious and trailblazing career. She was mentored by NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) founder Thurgood Marshall; cowrote briefs in Brown v. Board of Education; argued 10 civil rights cases before the Supreme Court; defended Martin Luther King Jr.’s right to march in Albany, Georgia; advocated for the admittance to the University of Mississippi of James Meredith ’68 when he was an undergraduate; and served as a New York state senator and the Manhattan borough president. One of the capstones of Motley’s career was being the first Black woman to serve as a federal judge when President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed her in 1966 to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

But until last year, there had never been a full-scale biography of the quintessential Columbian. So when Columbia Law School Vice Dean for Intellectual Life Kathryn Judge, Harvey J. Goldschmid Professor of Law, and Olatunde C.A. Johnson, Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 Professor of Law, began discussing the concept of a Community Book Read, they agreed that the 2022 book Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality by Tomiko Brown-Nagin was the perfect book to launch the series.

On October 11, Brown-Nagin, a Harvard Law professor and the dean of Harvard Radcliffe Institute, visited Columbia Law School to share insights into Motley’s life and discuss her process as a biographer. After introductory remarks by Judge and Gillian Lester, Dean and Lucy G. Moses Professor of Law, Brown-Nagin fielded questions from a panel that included Johnson; Petal Modeste, associate dean for professional affairs administration; and Alice Park ’25, president of the Empowering Women of Color student organization.

Brown-Nagin explained that she got the idea to write Civil Rights Queen when she was working on a previous book, Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement, and found there weren’t as many books and articles about Motley as there were on other key players in the civil rights movement. “Frankly, I knew that several of them had not quite achieved as much,” said Brown-Nagin. “And the key motivation here pertains to the question of why there was so little material on her, and I’m afraid it comes down to gender. It’s true of civil rights history just the same as it’s true of American history generally, and that is the folks who are lifted up as people of courage, people who deserve to be known and remembered, tend to be male.”

According to Brown-Nagin, Motley’s career is extraordinary, in part, because she affected social change by using her legal training in three distinct ways—as an impact litigator, a politician, and a judge. “[But] Constance Baker Motley would deserve a biography if she’d never been nominated to the judiciary,” said Brown-Nagin. “She was already a pathbreaker in these two other realms.”

Motley faced challenges and indignities, both large and small, every step of the way: as a lawyer traveling and practicing in the segregated South, as a politician with no prior experience, and as a judge whose decisions were scrutinized for possible bias because of her racial and gender identity. Even at the LDF, Motley had to contend with the sexism of the era. Marshall, who hired Motley, was “fascinated” by her, according to Brown-Nagin. “I’m sure many of you know, Thurgood Marshall was very charming. He was a storyteller. He had an informal kind of manner,” she said. “Now, I have to say that it wasn’t all fun, because Thurgood Marshall, I write in the book, like many men of the time, paid some attention to her looks and essentially took actions that would make us cringe today.”

Motley’s accomplishments, said Brown-Nagin, are remarkable by any standard: “It is more impressive what she was able to achieve given that she was fighting both gender and race discrimination.”

Motley also defied categorization. In the 1950s, when she started litigating civil rights cases, she was considered a radical, but “by the early 1960s, there were people who thought she was sort of conservative,” said Brown-Nagin. “She was thought to be sort of upper crust. She came from a household where, as immigrants from Nevis, her parents spoke with a British accent, so she spoke in a certain way. And, as I put in the book, whatever people conjure when they think about an authentic Black person, she wasn’t it.” Brown-Nagin explained that seeing Motley in this light “shows that Black identity is not monolithic, which is something else I’ve explored for some time in my work.”

As a judge, Motley was pragmatic rather than political. “She was judicious. She was careful. She was methodical,” said Brown-Nagin. “All things considered, she was pretty moderate. Now, I mean moderate for the Southern District of New York. I don’t mean moderate for the Southern District of Mississippi. ”

Brown-Nagin believes Motley is an enduring role model. “It is fascinating to see the world of law through her lens,” she said. “We’re living in a time, I believe, where we need inspiration, we need examples of people who experience setbacks, as she did, but she just kept going, and she kept going for us. And so when I feel down, I think, well, if Constance Baker Motley could keep going under her circumstances, surely I can, and we can, under our circumstances.”

After the program, student panelist Park reflected on the Community Book Read. “Reading about Constance Baker Motley’s career and impact as a civil rights lawyer reminded me of the power of the law to advance racial justice and pushed me to pursue this type of work,” she said. “I’m now externing at the Legal Defense Fund and am constantly inspired by Motley’s legacy, resilience, and commitment to justice. Motley paved the way for so many women and people of color, and I’m indebted to Dean Brown-Nagin for telling her story.”

The Community Book Read is part of the Lawyers, Community, and Impact Series. It was sponsored by the Office of Student Services, the Vice Dean for Intellectual Life, the Black Law Students Association, Empowering Women of Color, and the Columbia Law Women’s Association.