The Academic Side of RBG

Renowned for breaking glass ceilings, winning important victories for gender equality, and making history in the country’s highest court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s journey to becoming a legend started in the classroom.

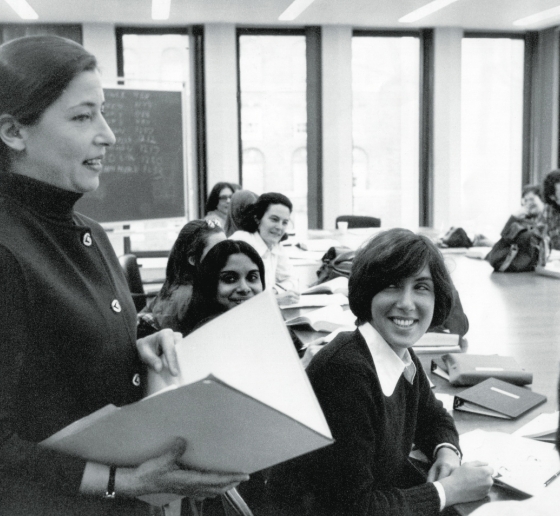

Above: Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 encourages students in her Columbia Law seminar on sex discrimination law to assist her in preparing to argue on behalf of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Throughout her career, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59 maintained a special bond with Columbia Law School. After graduating tied for first in her class, she became the first female tenured professor at the Law School and, later, as a judge, hired more than two dozen Columbia Law School graduates to serve in her chambers as law clerks (many of whom went on to become leaders in the legal profession). She also returned to campus for special events over the years, including one last time in 2018 for a celebration of the 25th anniversary of her investiture to the Supreme Court.

Read more about Justice Ginsburg’s long history with Columbia Law below: