Sentencing

Does the punishment fit the crime?

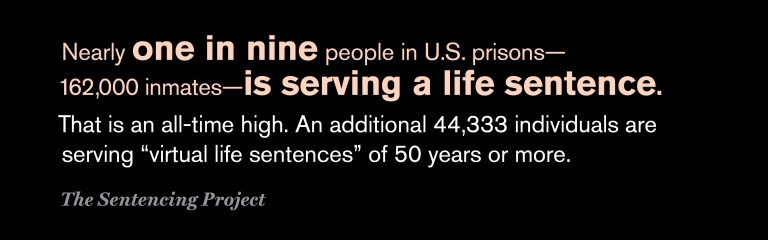

Should a rapist go to prison for two years, five years, or life? Should an embezzler serve one year or 10? Policymakers, legislators, prosecutors, and judges share responsibility for the length of criminal sentences and the growth of state and federal prison populations by 350 percent from 1980 to 2016. The rise is attributed in part to changes in mandatory minimum sentencing policies.

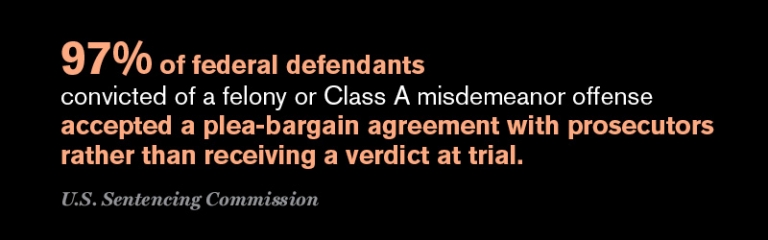

Professor Daniel C. Richman, a former federal prosecutor, explored the topic in his essay “Accounting for Prosecutors,” published in Prosecutors and Democracy (Cambridge University Press, 2017). Since prosecutors decide what charges to bring and against whom, he says, they in effect define criminal law.

In Richman’s seminar on sentencing (which he teaches with Judge Richard Sullivan of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit), students consider the purposes of prison sentences: keeping criminals off the streets, deterring crime, and providing retributive justice. “Retribution sounds medieval because people think of vengeance, but you can think about it in terms of moral deserts,” Richman says.

Discussions about sentencing reform often focus on reducing mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenders, who comprise just 20 percent of the overall prison population. By contrast, 50 percent of the prison population is serving time for violent crimes, including aggravated assault, kidnapping, murder, and rape.

“You could release the entire population of drug offenders across American jurisdictions, and it wouldn’t change America’s status as the world leader in incarceration,” Richman says, though he adds that the harsh realities of the drug trade must still be addressed.

“Until we figure out how long it is appropriate to keep violent offenders in prison,” he continues, “we’re not going to have serious sentencing reform.”

“The conservative case for reform is obvious: Spending billions of dollars on prison expansion and lengthy sentences is outdated and ineffective. And the state level is where reform will be the most effective—the majority of people are incarcerated in state systems.” —Brandon Garrett ’01, author of Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong and a professor at Duke Law School, in Slate